Angela Lammert on

Terry Fox

So after 30 years I’m still working on the aspect of redefinition of sculpture. TERRY FOX, 1999[1]

The American-European artist Terry Fox (1943–2008) considered all that he created to have expressed his search to realize an extended concept of sculpture. He used his body as sculptural material in just the same way as he employed sound or text in performance pieces, for which he—to distinguish them from the increasing commercialization of performance art—coined the term “situation.” In the seventies these situations were accompanied by videotapes, which he then turned away from around 1980 to concentrate on working with sound. In the first half of the seventies, many artists were committed to establishing video and film as recognized mediums in the visual arts. Although Fox is not to be counted amongst them, his video works not only document his haunting, almost meditative performances, but they also possess an intrinsic value for the specific medium itself.

The video pioneer David Ross, whom Fox purposefully invited to his video exhibitions in the seventies, provocatively claimed: “If there ever was such a thing as a video artist, it wasn’t Terry Fox.”[3] For Ross, Fox was a conceptual artist who “wanted to pare down his work to its material and formal essence” and thus saw video as a means for extending his performance pieces. In a 1971 interview with Willoughby Sharp, the founder of Avalanche, there is a revealing exchange: “People won’t really fully understand the piece unless they watch you perform, or see a videotape of it.” Terry Fox answers: “Right. Photographs are inadequate, but a videotape would show you what happened.”[4] For the director of the Berkeley Art Museum, Brenda Richardson, who prepared Terry Fox’s first museum exhibition in 1973, the videos have the status of artworks: “In the past few years it has become accepted fact that photographic and video documentation of performance pieces assume the status of art objects […] there will also be exhibited videotapes made by Fox, the latter a photographic art form which Fox has developed with great success.”[5] The function of the media remained very ambivalent however, in particular amongst the artists themselves. Indisputable is how video and sculpture—the moving image and space—overlap. And Terry Fox is no exception, repeatedly exploring the relationship of the new medium to his performances up until the early eighties.

Turgescent Sex, 1971, video stills © Terry Fox, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

One of his first and often shown videos is Turgescent Sex (1971), a work with references to the Vietnam War. Fox wanted to post the videotape like a letter.[6] During this performance for the camera, the viewer observes the artist, blindfolded, tying a rope around a fish, enwrapping it with slow ritual gestures. His friend and fellow artist George Bolling shot the video in Fox’s San Francisco studio. On a sheet of notepaper now in the archive of the de Saisset Museum in Santa Clara, Bolling has jotted down: “documentation of a performance.”[7] Sound and lighting are not mentioned. In contrast, Terry Fox’s own description, given in a brochure from 1976, includes the sound as an element determining the space: “The sound is the flow of traffic outside my door, the light is the sunlight on my floor.”[8] The everyday noises represent in the video the desired transgressing of the boundary between art and life, an act Fox performed metaphorically in his “situations.” The video performance in his American studio is turned into two pieces at symbolic locations in Europe the following year: performed in 1972 under the title Pont at the Sonnabend Gallery in Paris and under the title L’Unita at the Lucio Amelio Gallery in Naples. The video and both “situations” differ because of adaptations made to fit in with the respective venues and the distinctive involvement of the respective audiences.

Children’s tape, 1974, video stills © Terry Fox, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

In Turgescent Sex, as in Fox’s video Children’s Tapes (1974), the sense of space is generated by zooming and remote setting of the camera. Fox developed Children’s Tapes as an alternative to television for his son. Varying in length (from one to seventeen minutes), the tapes show in close-up the handling of simple objects and how physical phenomena are subject to transformation processes. Playfully they reveal an unconventional humor, a joy at the unexpected. The production was undertaken for David Ross, who included Children’s Tapes in the traveling video exhibition Circuit of 1973, which was shown by Wulf Herzogenrath at the Kölnischer Kunstverein. In a video message produced in 2015, Vito Acconci, a friend of Fox’s, paraphrased the artist’s comment published in a magazine at the time the work was created: “Video is a tool, camera on a tripod 3½ feet away, I zoom all the way to get it in focus, then zoom it back out, put the objects down so I can see how the new situation is set up, then I zoom all the way out or all the way in.”[9] From a present-day perspective, Children’s Tapes seems to anticipate the well-known film The Way Things Go (1987) by Peter Fischli and David Weiss. Employing an extreme close-up for three-dimensional objects—which Fox also shot from a bird’s-eye perspective—seems to correspond with minimalist sculpture. At the same time, the video is connected to the basic themes of his work: with the labyrinth as a metaphor of his life as well as demonstrating phenomena and their transformations. Fox first comes up with the “situations” and only then as a consequence strikes on the idea for the videotapes. His sense for spatial arrangements is also evident in the first exhibition presentation of the tape on two screens positioned opposite one another. In 2002 the individual tapes were shown on several screens in a department store as part of the Fluxus exhibition 40 Jahre: Fluxus und die Folgen in Wiesbaden and could be seen simultaneously at the opening in the museum as a large-format projection with a beamer.

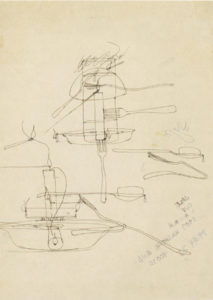

Terry Fox, sketches for Children’s Tapes, 1974

While Fox experimented with spatial arrangements and the generated effects in performances produced for the camera, in other video works created concurrently he explored the materiality of the medium. Here the aesthetic of soft focus plays an important role. And this as early as 1971, right at the very start of his experiences with the medium of video. The setting of The Rake’s Progress (1971) resembles an experimental setup, and Terry Fox is seen applying grease to a screen and then wiping it off again.[11] The preparations are recorded on video and are part of the work. One sees and hears George Bolling, Fox’s twin brother Larry, and the director of the de Saisset Museum, Lydia Modi-Vitale, who was one of the first directors to work with video recordings of performances, while music by Bob Dylan plays in the background. The work is thus neither a documentation nor a presentation of changing camera settings as in Turgescent Sex, but more of a game with the peculiarities of the medium. Standing with his back to a mirror, Fox coats the screen with the grease in such a way that not only a cloudlike, fuzzy image filling the whole format results, but thanks to the camera’s reflector a doubling effect is simultaneously produced. In the following camera setting on the television screen, one sees Fox removing the grease with a rag and not applying it as in the initial shot, while the earlier videotape is played back slowly.

In his video Incision (1973), Fox radicalizes the effect of soft focus by employing a special lens. A plaster model of the floor labyrinth in Chartres Cathedral—he had discovered the labyrinth in 1972 as an apt metaphor for life—is mapped spatially and haptically with the camera. Operating the camera, Fox is not to be seen throughout the video. The camera approaches the flat object with its labyrinth incisions, and it slowly fills out the whole format as a fragment. The video image outside the inner circle becomes increasingly blurry. The camera continues to move, following the incisions. The video is accompanied by atmospheric sounds which Fox produced on a self-built instrument. The video ends with a completely unfocused shot. In Fox’s search to realize an extended concept of sculpture, performance comes to possess a spatial quality for him, just like sculpture and his video works. One could even say that depicting movement in space through the video becomes a performance of space itself. This is why he built the plaster model for performing and videotaping. He had discovered the floor labyrinth in Chartres as a metaphor for existence, representing the path through life and movement in space and time—and not just as some fanciful garden maze. Because the object functions at once as a material and a mental layer for the tracking shot, the whole process of creating art becomes an artwork in the exhibition and for any other usage. The different iterations are part of a work understood as sculptural intervention, and are then also integrated into exhibitions. The plaster model used in the video is to be found in Fox’s 1973 exhibition at the Berkeley Art Museum, positioned on a panel along with other performance relics in the sight line to photographs attached to the wall. They are the result of a model of the performance space built by Fox, whereby he photographed the small objects he later employed in the performance. He positioned the photographs virtually as an interior view of the exhibition model, close together around the real space with the experimental setup on the panel.

The culmination of this interpenetration of space, sound, and video is the work Lunedi (1975), with Bill Viola behind the camera. For the video a studio performance carried out with Tom Marioni is repeated that had originated in connection with Marioni’s Museum for Conceptual Art in San Francisco. Space and image are generated by the sound, the camera following the sound resulting from a bow stroked up and down the edge of a metal bowl and the pattern that develops. As if from a distant view to a close-up—the video camera pans without capturing the performing artist’s face.

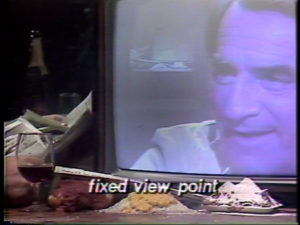

Flour Dumplings, 1980, video stills © Terry Fox, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

In 1980 Fox created what would prove to be his last video. Shot in color, Flour Dumplings elevates the headlines taken from radio news, worked into textual segments, into an element of a moving image. Fox’s view of video had changed: “[…] but video is similar to painting, it’s the same kind of restrictions. So you’re going to do a performance and use a tape and the longest tape you could get is an hour. And that’s really stupid, you know. You have all these equipment restrictions. You have a given technology and you are seeing what you can do with it. But you can’t do anything that the tape recorder can’t do.”[12]

Exhibiting a video is performing a video. At the same time, the presentation means conserving and changing the technologies of the recording and playback media. This makes other exhibition forms of historical video works possible. How does one arrange and stage an exhibition about an artist who can no longer be experienced with his performances and who operated between different media? Curated by Arnold Dreyblatt and Angela Lammert, the exhibition Elemental Gestures – Terry Fox, held at the Akademie der Künste, Berlin (2015/16), was thematically structured, for this was deemed the most feasible way to make his temporary way of working a sensory experience, to show how he dealt with recurring themes in the different media, and how radical his method, transcending media, was.[13] Inquiring into the relationship between video and sculpture, documentation and the intrinsic value of the medium, was one reason not to present videos on screens but to project them in large format with a beamer onto walls positioned separately and sculpturally in the exhibition space. Two aspects encouraged this presentation form. Firstly, in the seventies Fox’s videos were not only shown on screens but at times part of a video program. Secondly, already from a technological point of view it is difficult to exhibit video works using historical equipment. A historicizing performance or exhibition form can be problematic[14] because at times it can lead to a gratuitous staging and combinations between the video work and the presentation equipment. Thus, the specific case always needs to be considered when deciding which exhibition form does justice to the work. And this can vary from exhibition location to exhibition location.

The close relationship between sculpture, video, and space has the effect of shifting the boundaries between depiction and exhibition. Through video, depicting movement in space can become a performance of space, while the process behind presenting art in an exhibition can be a work of art. This is in particular the case for works spanning various media and where a changed understanding of sculpture is at work.

[1] Terry Fox (1999), in: Elemental Gestures – Terry Fox, ed. Arnold Dreyblatt and Angela Lammert, commissioned by the Akademie der Künste, Berlin, exh. cat., with the BAM – Musée des Beaux-Arts, Mons, the Von der Heydt-Museum Wuppertal, and the Kunstmuseum Bern. Dortmund 2016, p. 50.

[3] David Ross, in: ibid., p. 39.

[4] Terry Fox (1971), in: ibid., p. 252.

[5] Brenda Richardson to Security Staff, 5 September 1973, University Art Museum, Berkeley, archive, cited in: ibid., p. 59.

[6] Terry Fox (1976), in: ibid., p IX.

[7] George Bolling: Terry Fox “Turgescent Sex”, ca. 1971, in: ibid., p. XX.

[8] Terry Fox in: Anna Canepa Video Distributions Inc. Represents the Following Artists: Eleanor Antin, Terry Fox, Taka Iimua, Allan Kaprow, Les Levine, Dennis Oppenheim, Roger Welch. Distribution brochure, New York 1976, pp. 6-7, in: ibid., p. IX.

[9] Vito Acconci (2015), in: ibid., p. XII.

[11] The title refers to William Hogarth’s A Rake’s Progress, a series of paintings Hogarth completed in 1732-33 which depict the social decline of a “wanton” young man. Steve Seid: “Die Aufhebung: der (Un-)Gläubigkeit,” in: ibid., p. XIX.

[12] Terry Fox, It’s an Attempt at a New Communication, Interview by Robin White, in: Terry Fox. Ocular Language. 30 Jahre Reden und Schreiben über Kunst. Ed. Eva Schmidt, Bremen 2000, p. 91.

[13] Four spatially and thematically intermingling associative thinking spaces were evoked: Situations/Körperliche Zustände, Elements/Material, Mapping/Labyrinth, Sound as Sculpture/Raum als Instrument.

[14] One example is the exhibition shown at the ZKM in 2010, RECORD>AGAIN! – 40jahrevideokunst.de – Teil2, where the attempt was made to play back video works on monitors and television sets which themselves were museum pieces.